About Us

Our History

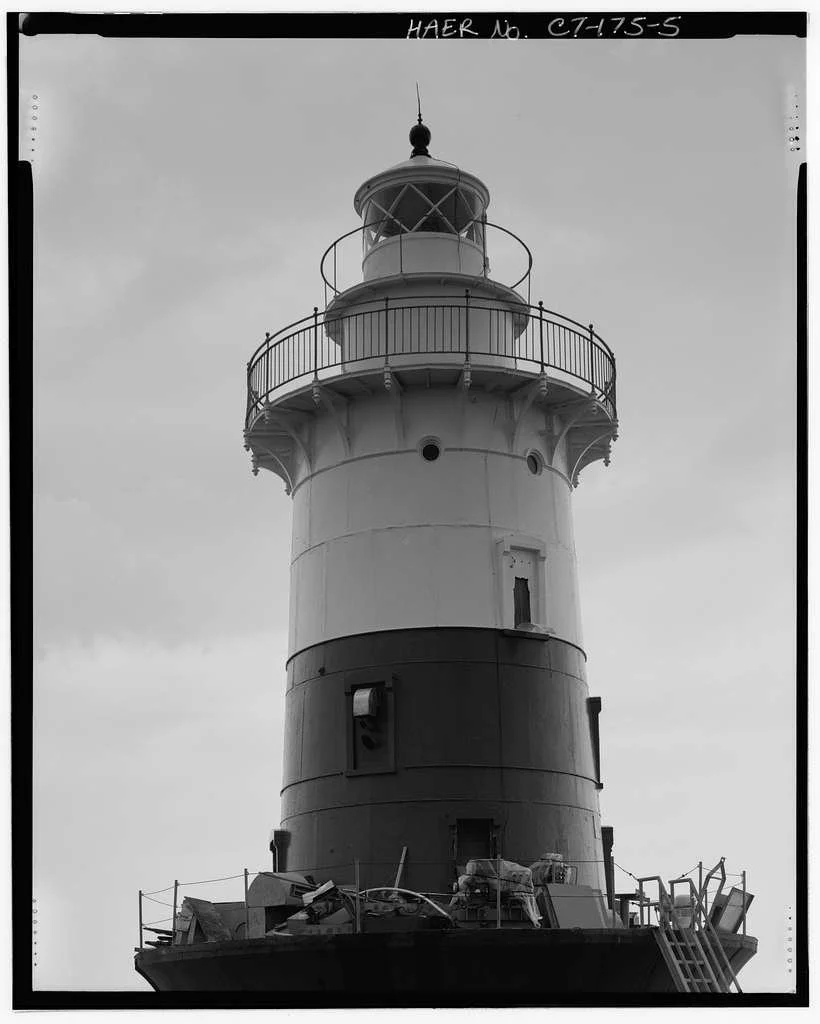

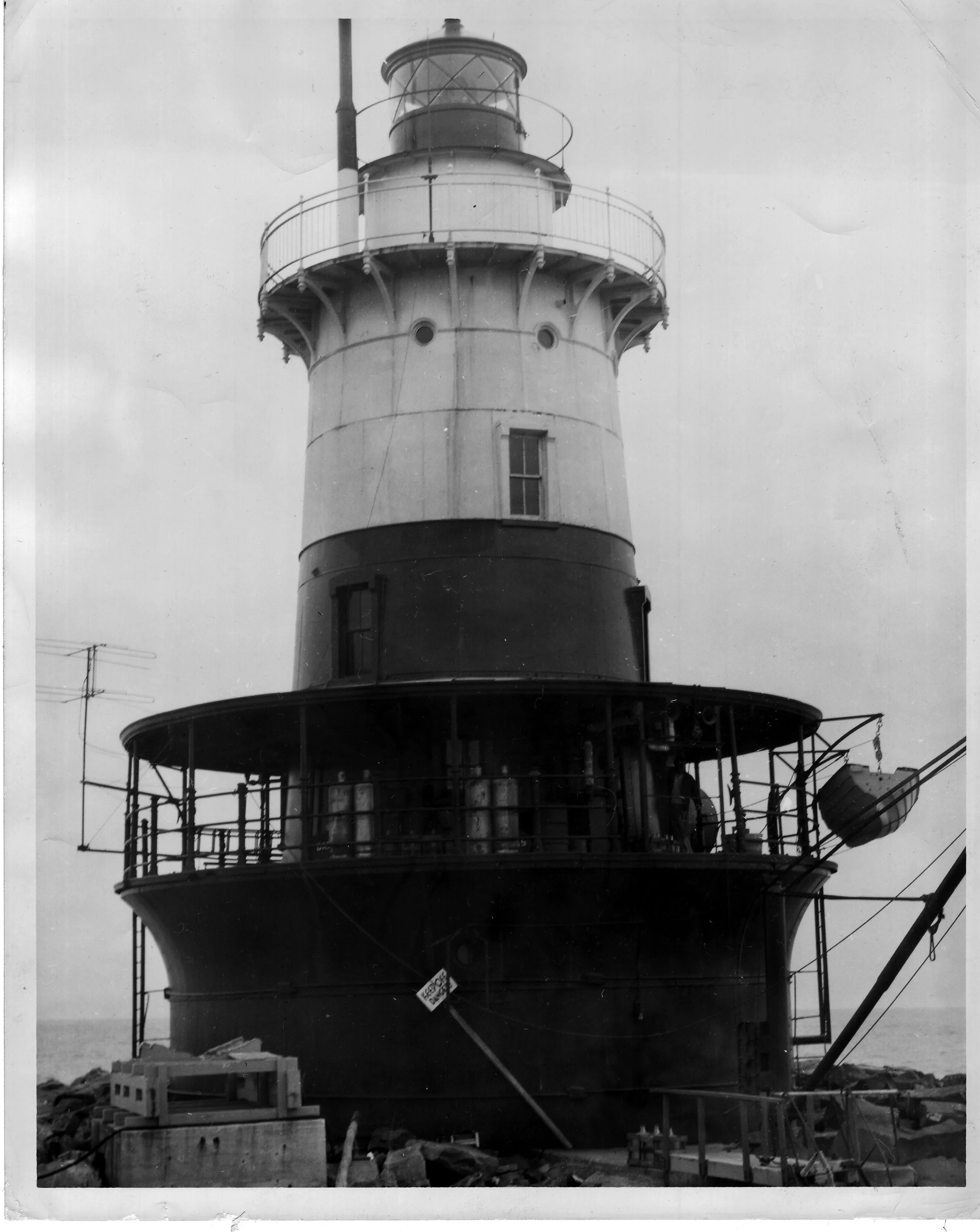

C onstructed in 1902 to aid the navigation of a bustling maritime route from New York City into Norwalk Harbor, the Lighthouse has become an iconic symbol of the Rowayton and Darien coastal communities with an illustrious history and enduring beauty that stands as a testament to resilience, illuminating the rich heritage and unbreakable spirit of the shoreline communities it watches over.

In times of peace and peril alike, it has stood as a silent guardian, a steadfast sentinel bridging the past and present. Its foundation was reinforced with 30,000 tons of granite from the excavation of Radio City Music Hall in 1932, which helped it withstand the devastating Hurricane of 1938. During World War II, it served as a strategic coastal defense post, monitoring for enemy submarines in protection of New York City.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Lighthouse has inspired generations of renowned artistic works, including masterpieces from Walter Dubois Richards and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Still operating as an active lighthouse, Greens Ledge is one of the only offshore lighthouses in the world that offers regular public tours and educational programming.

L egend has it that Greens Ledge (or 'Greens Reef' as it was known until the 1940s) was named after a pirate Green, who sailed with the infamous Captain Kidd. When Green was captured by authorities of the day, he was reportedly executed and his body fastened to the ledge in chains as a dire warning to others thinking of entering the buccaneering trade. Years later, a lighthouse would be established on the ledge as a warning to vessels seeking to enter Norwalk Harbor.

1800’s

A lthough severely damaged by fighting during the Revolutionary War, Norwalk, Connecticut became a bustling center for shipbuilding, manufacturing, and commercial fishing after the conflict. In 1826, Sheffield Island lighthouse commenced operation in Norwalk Harbor, but as the size and number of ships calling at Norwalk increased, additional navigational aids were needed. In 1896, the Lighthouse Board recommended that a lighthouse be placed on Greens Ledge, at the western end of a long and dangerous shoal extending from Sheffield Island. The construction of Peck Ledge Lighthouse just to the north of Sheffield Island was proposed at the same time, along with the placement of five post lanterns to mark the shipping channel in the harbor.

Early 1900’s

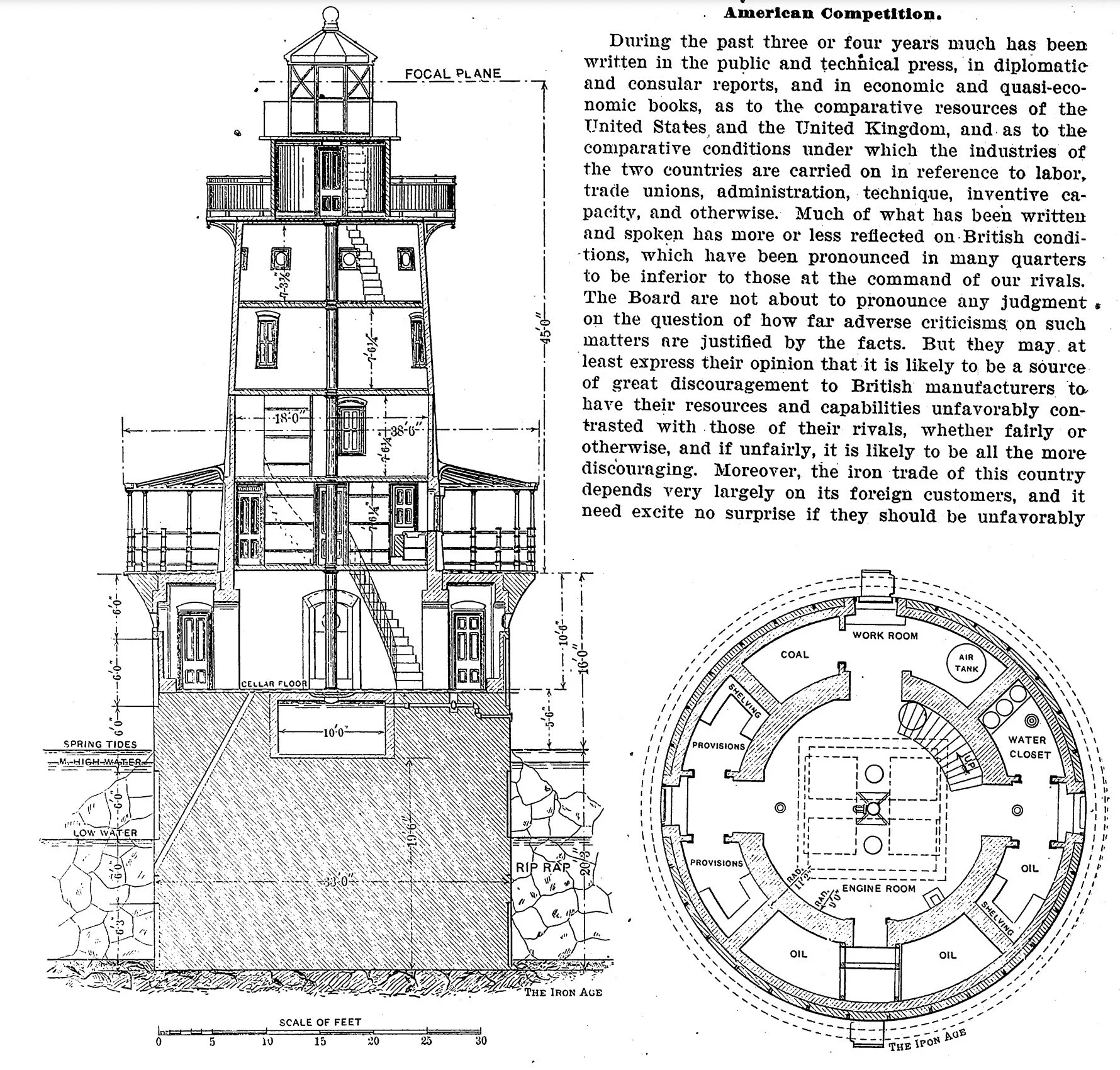

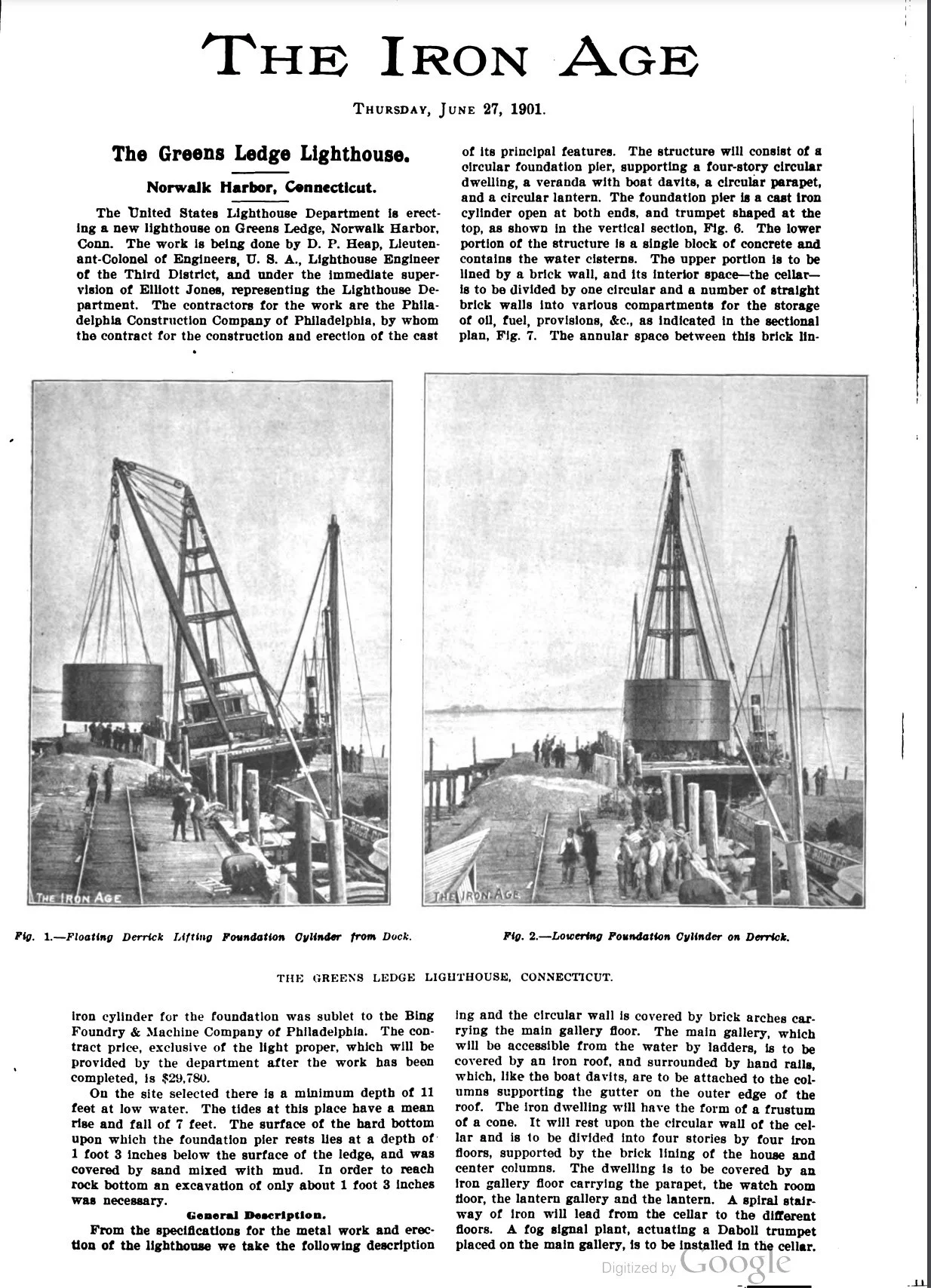

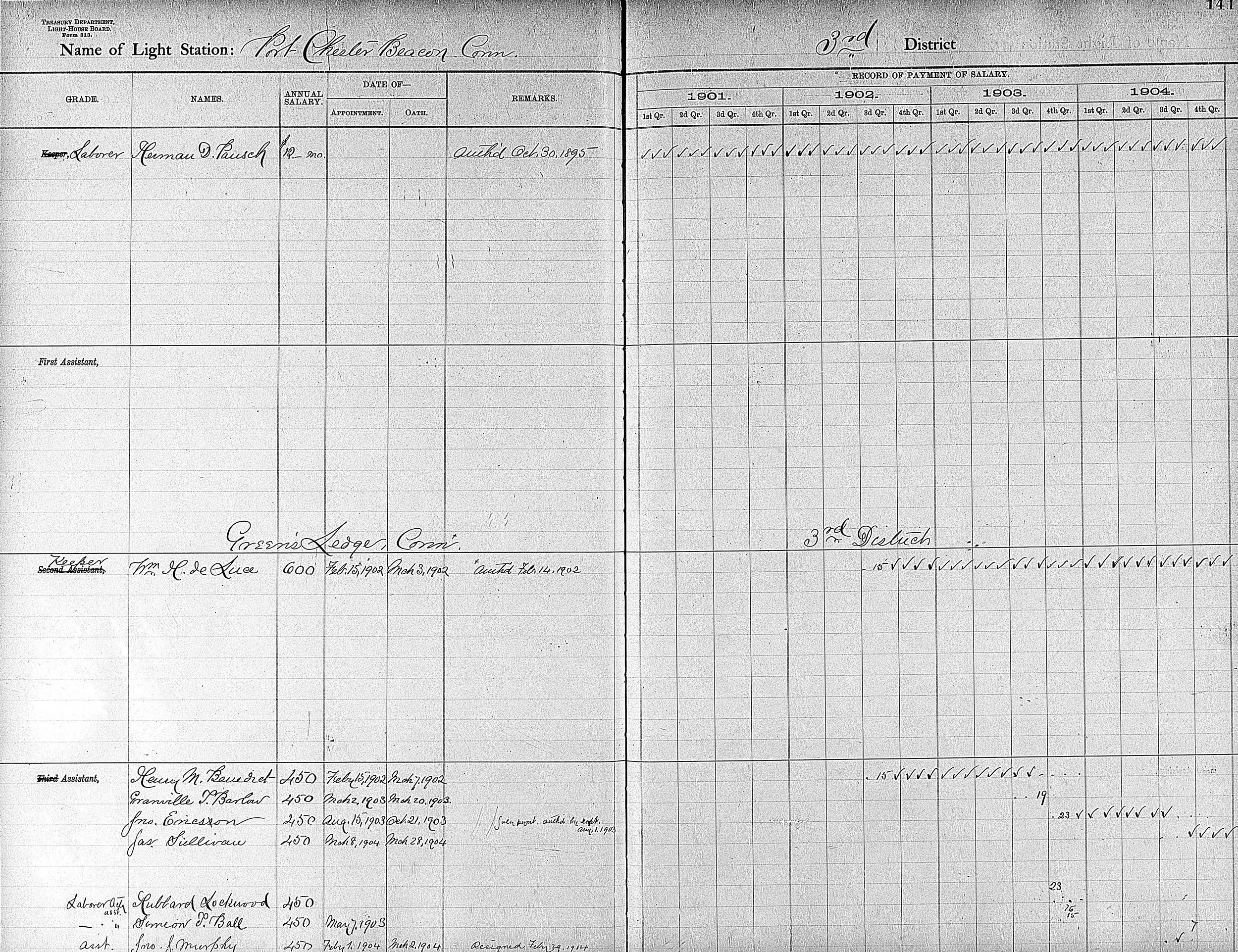

C ongress provided $60,000 for construction of Greens Ledge Lighthouse in an act approved on March 3, 1899, and the Lighthouse Board announced that sealed bids for the necessary metalwork and for the erection of the tower would be received until August 7, 1900. Philadelphia Construction Company was selected as the contractors for the work at a cost of $29,780, and they sublet the construction and erection of the cast-iron foundation cylinder to the Bing Foundry & Machine Company of Philadelphia.

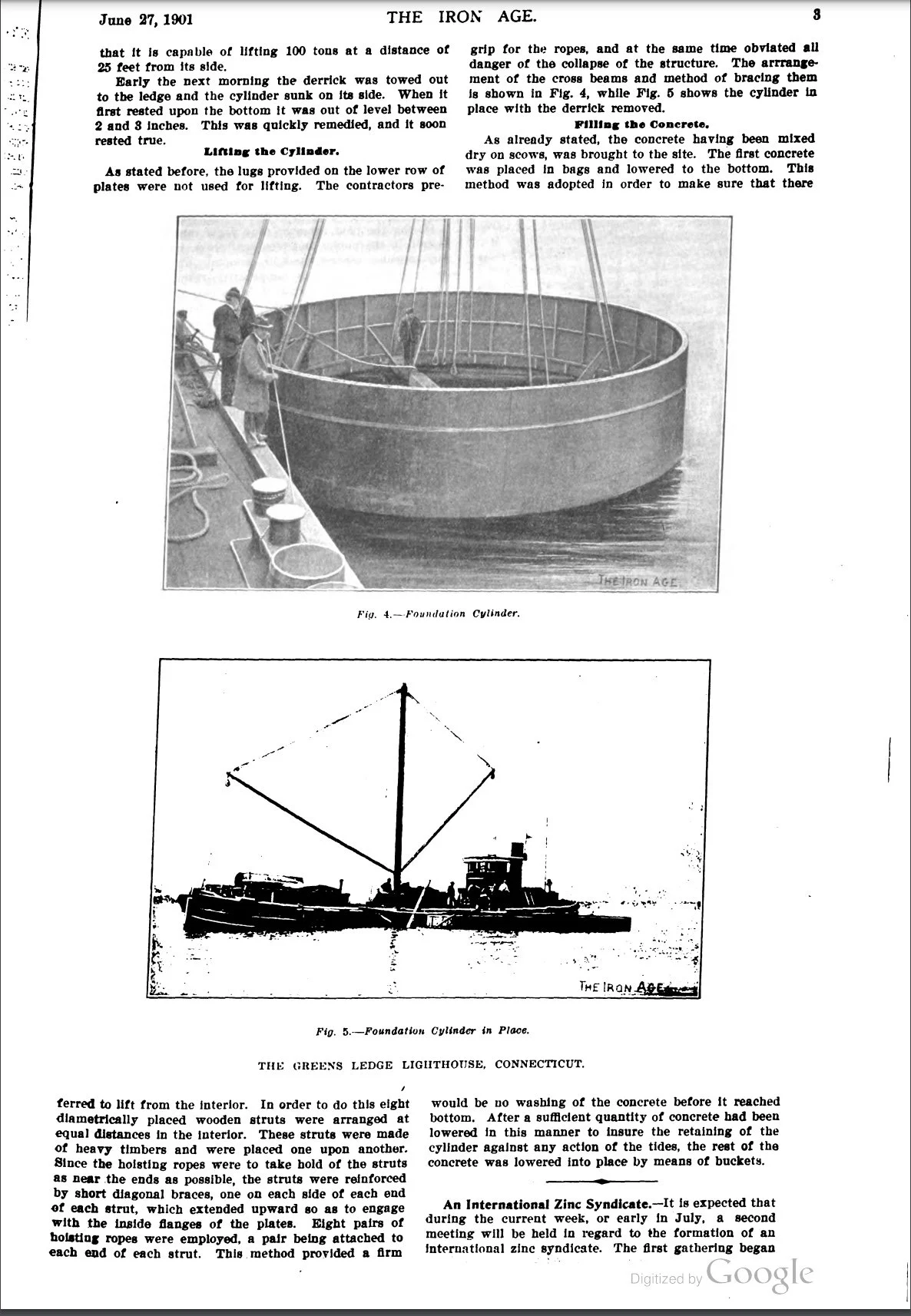

The foundation cylinder is just over thirty-nine feet tall, while the tower is thirty-two feet tall and tapers from a diameter of twenty-one feet at its base to seventeen feet at the lantern room. The foundation cylinder was placed on the mammoth floating derrick Century on the afternoon of May 21, 1901, and early the next morning the derrick was towed out to Greens Ledge and the cylinder was sunk in place. By July 28, 1901, the foundation had been partially filled with concrete and lined with brick. The first and second courses of the tower were set on August 9 and 10, and the entire work was completed on October 31, 1901. Some 1,500 tons of riprap were placed around the tower for protection, and the Diaphone fog signal plant, consisting of two five-horsepower oil engines and two air compressors, was installed in January 1902.

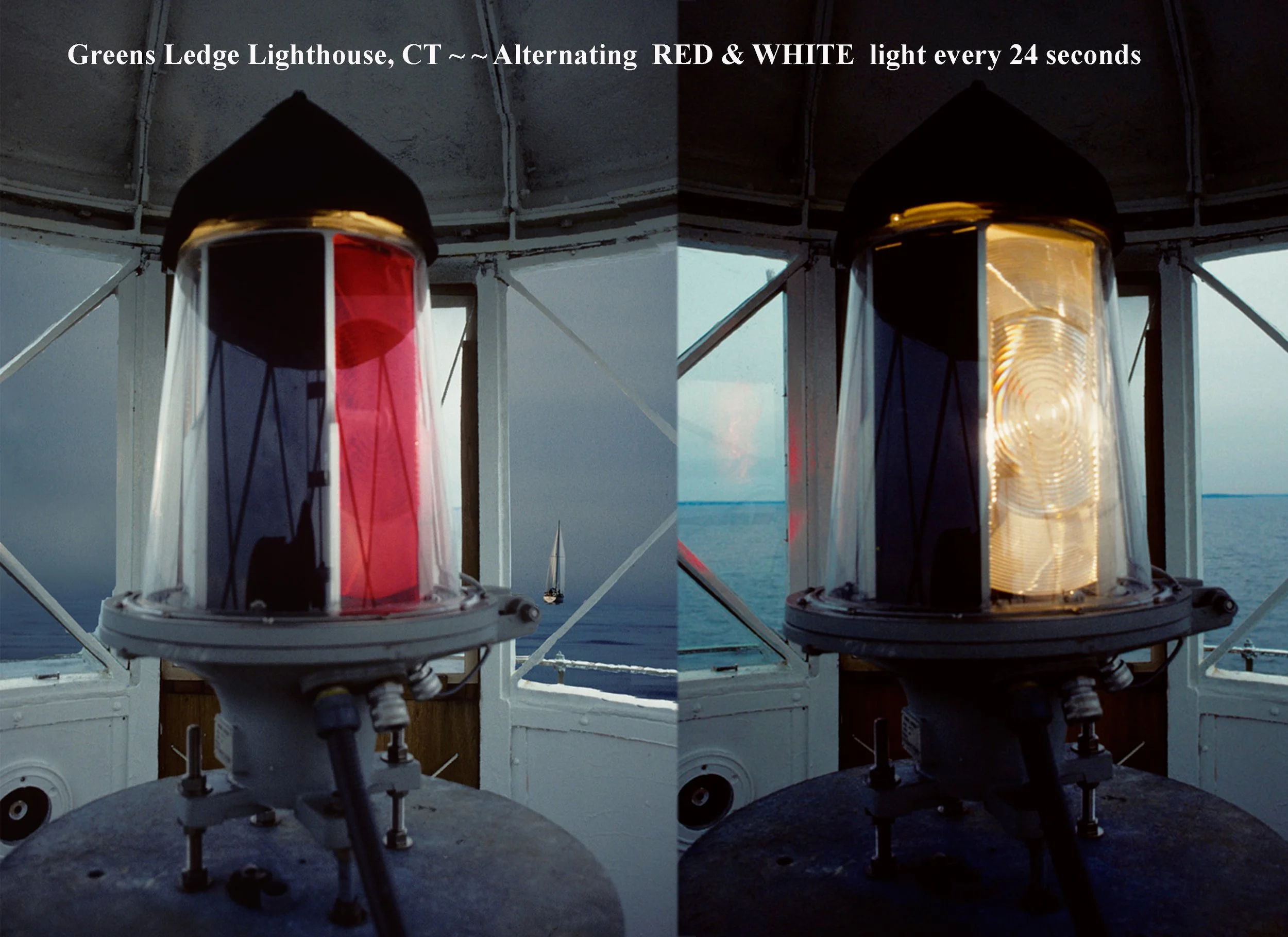

A temporary fifth-order lens, which produced a red flash every fifteen seconds, was installed in the lantern room on February 14, 1902 and placed in operation the following day. No longer needed, the nearby lighthouse on Sheffield Island was discontinued. The temporary fifth-order light served until mid-May when a fourth-order lens was installed, changing the characteristic of the light to a fixed white light varied every fifteen seconds by red flashes. The fog signal sounded three-second blasts separated by alternate silent intervals of two and thirty-two-seconds and was typically in operation about 400 hours each year.

Iron towers proved to be an efficient and low-cost method of building offshore lighthouses. Most of these “spark plug” lighthouses were located in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic States, although there was at least one in Texas (Sabine Bank, which was demolished in 2002). Offshore lights such as these required constant and vigilant maintenance, and so before the recent interest in lighthouse preservation, deactivated stations were quickly torn down. Even today, those wishing to restore and maintain a spark plug lighthouse face a daunting task, since the iron buildings rust and deteriorate quickly if they are not regularly painted. The lighthouses are also exposed to constant waves, ice in the winter, and even an occasional bump by a ship, which all take their toll on the structures.

On March 1, 1910, Keeper John Kiarskon took the station’s only skiff and went ashore, leaving Leroy C. Loughborough, his assistant, in charge of the light. Keeper Kiarskon was supposed to be gone for just a few hours, long enough to cash Loughborough’s $49.69 paycheck and procure some supplies, but he never returned to the station. Instead, Kiarskon cashed his assistant’s paycheck, checked into a local hotel, and went on a drinking binge.

Left alone, Loughborough dutifully minded the light, and when fog settled in for nearly four days, he was forced to operate the fog signal too and go without sleep for most of that time. Loughborough’s only companion was his dog, Sadie, and when supplies got low, the two subsisted on half rations until they split the last stew of meat and vegetables on the ninth day. The small sloop Tecumseh finally noticed something was wrong with the light and reported the matter. The lighthouse tender Pansy, under the command of John Haywood, set out for Greens Ledge, where Haywood found Loughborough unconscious on the floor near the fog signal with his faithful Sadie curled up beside him.

I would not go through that experience again for the United States mint. Several times I inverted the flag on the mast, intending to attract the attention of some passing boat and thereby escaping to the mainland, but the greater part of the time, it was so stormy or foggy the signal could not be seen…It would not have been so bad save for the awful fog, which made me keep at the engines night and day. It is well that the Pansy came when she did. I don't think I would ever have moved from that rug.

— Assistant Keeper, Leroy C. Loughborough, on his experience and eventual rescue from Greens Ledge Light

K Keepers at Greens Ledge participated in numerous heroic rescues of the victims of boating mishaps in the waters surrounding the station, but one assistant keeper named Frank Thompson found himself in a life-threatening situation one cold winter afternoon in 1917. Thompson had taken a rowboat to shore to get supplies. He left on his return journey at about 1:00 p.m., but was delayed by being forced to detour a number of times around ice floes in the harbor. As darkness approached, Thompson realized that he was still only halfway to the lighthouse, and he became trapped inside a large ice field, drifting with the tide toward open sea.

Fortunately a resident of South Norwalk named Charles Mills had been watching Thompson’s predicament from the shoreline and made some quick calls to the Lighthouse Service and local port authorities. The harbor was completely covered in ice by that time, preventing most vessels from leaving the harbor. The Bridgeport Towing Company was finally convinced to send a tug out to try to rescue Thompson, but only after collecting a $50 fee for the service. At 10:30 p.m. the tug located the cold and hungry keeper and returned him to Greens Ledge.

The Roaring 1920s & 1930s

P erhaps one of the more indeleable images from F. Scott Fitzgarald's seminal work The Great Gatsby is the green light that Gatsby watches across the water. Recent scholarship suggests that the inspiration behind that iconic green light may not have been the color green, but rather "Greens Light."

During the early drafting of the novel, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald spent the summer of 1920 honeymooning in a rented home in Westport, Connecticut – which is where the Fitzgeralds would meet the man believed to be the inspiration for Gatsby himself.

Everyday, Zelda would leave their Westport cottage and cut across the 175-acre estate belonging to their neighbor, mysterious multimillionaire F.E. Lewis, on her way to swim at Compo Beach. At night, Lewis would throw extravagant parties. Like something out of The Great Gatsby itself, one party even featured camels, elephants, vaudeville acts and a cowboy and Indian show. The two wealthy showmen even shared some celebrity guests: including theatrical producer David Belasco and John Philip Sousa.

Indeed, according to the book Boats Against the Current: The Honeymoon Summer of Scott and Zelda by Richard Webb Jr., West and East Egg aren’t in Long Island afterall, but instead are far more consistent with the Fitzgerald’s honeymoon home in Westport, Connecticut.

They found other clues that the atmosphere of Westport pervaded “Gatsby” in the railroad station, the bridge across the Saugatuck River, the buildings on the beach. Even paths that seemed to fit Fitzgerald’s descriptions, like one that crossed the estate next to the gray house.

Furthermore, in his film ‘Gatsby In Connecticut: The Untold Story’, Webb posits that the “The Great Gatsby” wasn’t the only Fitzgerald novel that drew heavily on influences from his summer spent on the Connecticut coastline. The 1922 Fitzgerald novel The Beautiful and the Damned, draws on the towns of Westport, Norwalk and Darien as inspiration for its setting.

While green lights were rarely used as aids to navigation before the 1930s, there is one light that may have left a lasting impression on Fitzgerald. Not green, but “Greens,” the light from Greens Ledge Light – roughly 5 miles southwest from the nearby beachfront.

Certainly, the Lighthouse would have been the most visible beacon in F. Scott’s view from Compo Beach towards the glowing Manhattan skyline and also his permanent residence in Great Neck, Long Island. Known as “Greens Light” to many of the locals, there remains a distinct possibility that the initial inspiration for Fitzgerald’s green light came from “Greens” Lighthouse.

Scott and Zelda are also believed to have visited the nearby Roton Point Amusement Park on at least one occasion, which in the summer of 1920 was at the height of its popularity, with more than 10,000 visitors per day to the park grounds. Equipped with two roller coasters, a Ferris wheel, a casino, and dozens of other attractions, the park was among the largest in the Northeast and hosted live concerts - including from Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway - along with the Miss America beauty pageant.

Operating from 1880 through 1940, steamships en route from New York City would receive signals to proceed into the harbor by Greens Ledge Keepers. Once at Roton Point Amusement Park, steamships, including the park's own Belle Island, would line up, sometimes five abreast, at the dock ready to unload thousands of passengers. Once at the park, postcard exchanges were among the most popular activities - many of which featured the nearby Lighthouse - while other visitors would sail or swim to the Lighthouse, which is roughly one mile from the Roton Point Beach.

In 1933, Greens Ledge Lighthouse received much-needed structural support following several damaging storms and winter ice damage over its then-three-decade history. 30,000 tons - over 60 million pounds - of granite stone from the excavation of Radio City Music Hall in New York City was used to construct the 125-foot crescent shaped breakwater “rip rap” around the Lighthouse .

The newly added rip rap may very well have saved the Lighthouse from collapse during the Hurricane of 1938, also known as the Great New England Hurricane, which was a devastating storm that caused widespread destruction along the East Coast of the United States. Greens Ledge Lighthouse faced the full force of this powerful hurricane which resulted in wind gusts in excess of 125 miles per hour and . wave heights that dumped seawater as high as the the fifth story window. Despite the immense challenges, the lighthouse managed to survive the onslaught, a testament to its sturdy construction and the resilience of the structure.

The storm struck with little warning, catching many residents and vacationers off guard. The powerful winds, storm surge, and flooding caused widespread destruction and tragic loss of life. Nearby Roton Point Amusement Park suffered catastrophic damage by the storm - including the complete destruction of both of its roller coasters and ferris wheel - that ultimately led to the closure of the park by the start of World War II several years later.

1940s-2000s

G As World War II engulfed the world, Greens Ledge Lighthouse assumed a new and critical role in the defense of the United States. Its strategic position near the entrance of the harbor made it an ideal location for coastal surveillance and protection against potential enemy threats. The lighthouse was equipped with a small contingent of Coast Guard personnel who operated a radio station and monitored maritime activities in the area. The Coast Guard personnel stationed at Greens Ledge Lighthouse played a crucial role in monitoring and reporting any suspicious activities occurring in Long Island Sound. They kept a constant vigil, scanning the waters for enemy submarines or vessels attempting to breach American defenses. Their dedication and tireless efforts were instrumental in maintaining the security of the region.

During World War II, coastal areas in the United States implemented strict blackout measures to minimize the chances of enemy ships or aircraft spotting the shoreline. Greens Ledge Lighthouse served as a significant asset in enforcing these blackout regulations. The powerful light of the lighthouse was extinguished, preventing any potential navigational aid for enemy forces and ensuring the safety of the surrounding area. Alongside its defense duties, Greens Ledge Lighthouse continued to guide maritime traffic, assisting ships in navigating the challenging waters of Long Island Sound. Its powerful light, although dimmed during blackout hours, helped steer vessels safely through the treacherous sea lanes, ensuring that commerce and vital supplies could reach their destinations during wartime.

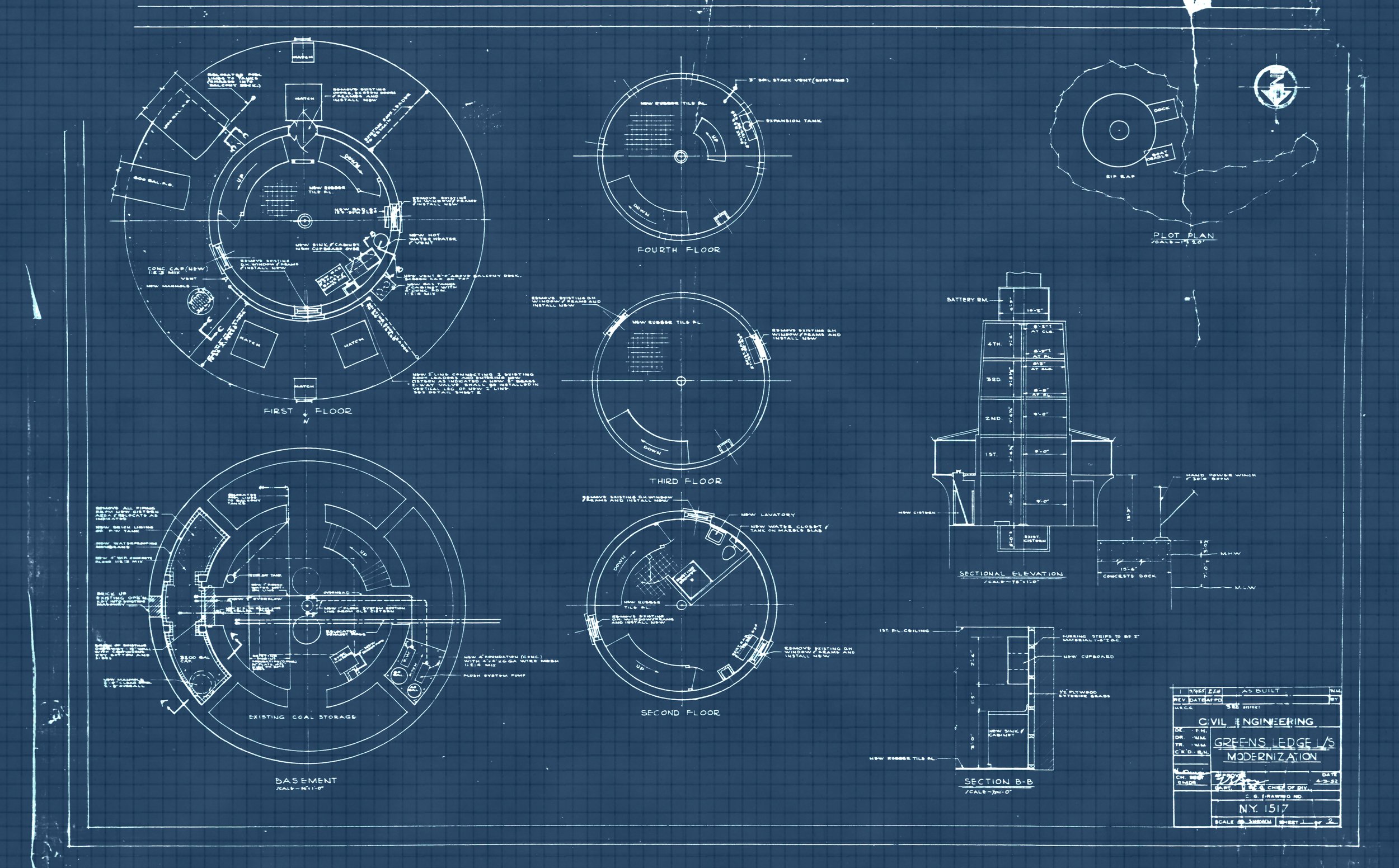

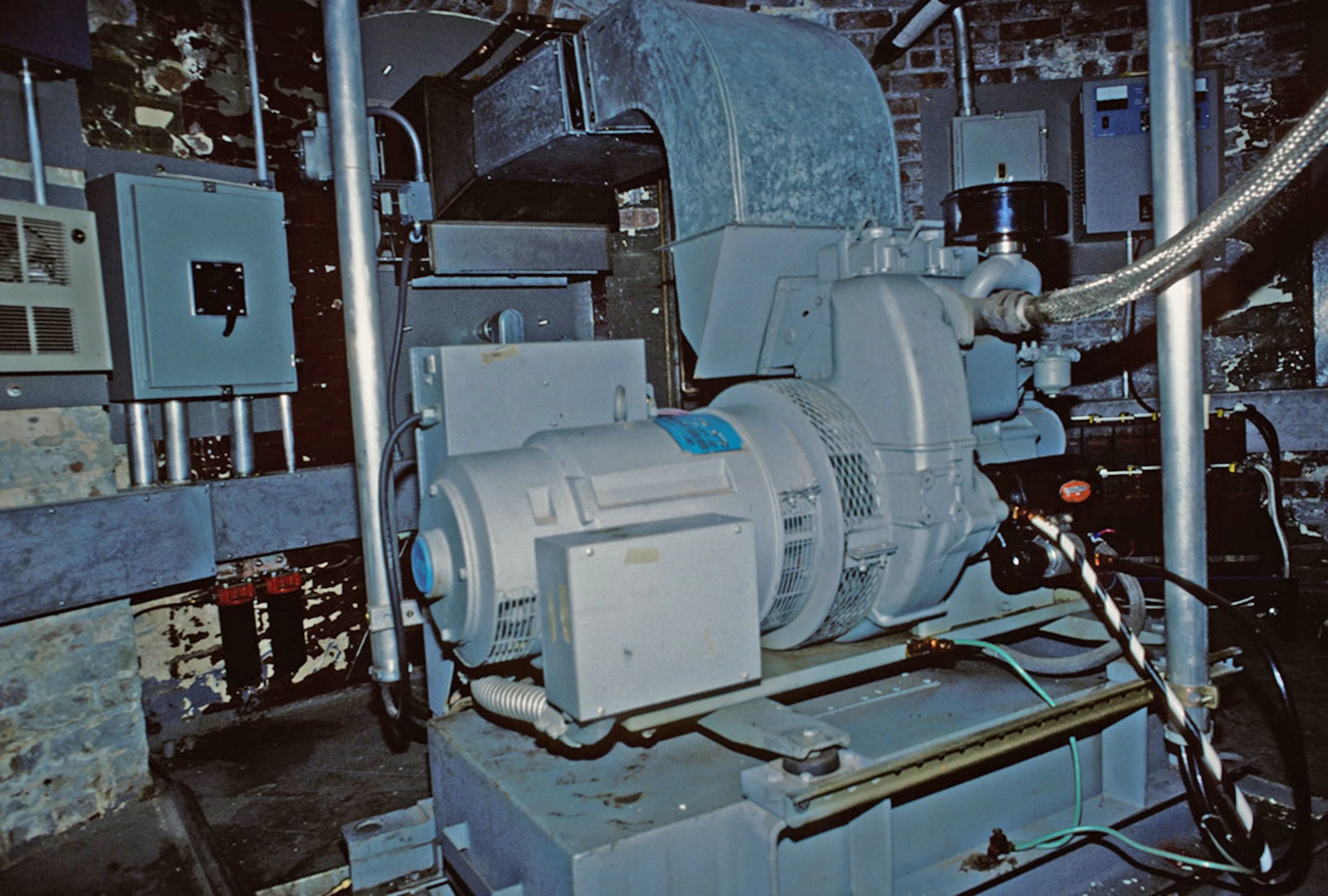

In the 1950s, the United States Coast Guard embarked on an ambitious modernization project for the Green Ledge Lighthouse. Situated off the coast of a bustling seaport, the lighthouse played a crucial role in guiding ships through treacherous waters. The project aimed to update the lighthouse's infrastructure and enhance its navigational capabilities to meet the demands of increasing maritime traffic.

The modernization efforts focused on several key aspects of the Green Ledge Lighthouse. First and foremost, the Coast Guard replaced the outdated lighting system with a state-of-the-art beacon that provided a more powerful and reliable light source. This upgrade significantly improved visibility for mariners, especially during inclement weather conditions. Additionally, the lighthouse's electrical system underwent a comprehensive overhaul, ensuring uninterrupted operation and enabling remote monitoring and control from the coast guard station.

Furthermore, the modernization project introduced advanced communication systems to the Green Ledge Lighthouse. The Coast Guard installed radio equipment that allowed lighthouse keepers to stay in constant contact with passing vessels and the coast guard base. This development greatly enhanced the efficiency of maritime communication, enabling faster response times to emergencies and improved coordination of vessel traffic. The upgraded communication capabilities not only bolstered the lighthouse's role in guiding ships but also contributed to overall maritime safety in the region.

The Coast Guard automated the light and fog signal in the 1972, but even today a weekend sailor occasionally runs aground on the shoal between the two lighthouses at Greens Ledge and Sheffield Island. The large boulders in the area around Greens Ledge are a favored home for lobsters and blackfish, and so also a favorite place for fishermen and divers. Greens Ledge Lighthouse was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1990.

2000’s - Today

I n August 2016, Green's Ledge Light was put up for auction to the public. It was sold on September 15, 2016 for $150,000 to The Pettee Family, the highest of four bidders. The Pettee Family donated the lighthouse to a newly founded 501(c)(3) nonprofit, The Greens Ledge Light Preservation Society, to spearhead the restoration and preservation efforts

Founded by local residents Tim Pettee, Alex Pettee, Shannon Holloway and Brendan McGee, the Greens Ledge Light Preservation Society was formally organized on September 30, 2016.

With Tim Pettee serving as President of the newly-formed nonprofit, the entity secured the rights to the underwater lands from the State of Connecticut on April 10, 2017 and completed the acquisition of the lighthouse when the quitclaim deed was executed with the Government Services Administration on May 17, 2017.

In September 2017, the group launched the 'Save The Light' campaign to raise $2 million to preserve and protect Greens Ledge Light. The major restoration work - the most significant in the history of Greens Ledge - began in 2018 and was completed in 2022. Restoration and renovation efforts are currently ongoing with a soft launch in the 2022 season and the lighthouse hopes to fully operational for expanded programming by the summer of 2023.

Interested in Helping Us Continue Our Restoration Work?

Gallery: Greens Ledge Through the Years

Keepers At Greens Ledge Lighthouse

Principal Lighthouse Keepers

William H. De Luce (1902-1904)

Robert Buske (1904-1909)

John Thorwald Kiarskon (1909-1910)

William T. Locke (1910-1915)

August F. Biedermann (1915-1916)

George Petzolt (1930-1932)

Stanley H. Fletcher (1960-1960)

John P. Jennings (1960-1962)

Robert J. Bonenberger (1962-1963)

Russel F. Brown (1963-1963)

Robert S. Hommel (1963-1964)

Jackie D. Keasler (1964-1967)

Robert S. Hommel (1967-1968)

Howard S. Matsuba (1968-at least 1969)

William F. Rhodes (at least 1917-at least 1920)

Harry C. Fox (at least 1921-at least 1922)

Thomas J. Murray (at least 1925-1930)

Manuel Resendes (at least 1935- )

George H. Clarke (at least 1936-1943)

Oscar L. Garfield (at least 1969-1960)

1st Assistant Lighthouse Keeper

Henry M. Bevedret (1902-1903)

Hubbard C. Lockwood (1903-1903)

Simeon T. Ball (1903-1903)

Granville T. Barlow (1903-1903)

John Ericson (1903-1904)

John J. Murphy (1904-1904)

James Sullivan (1904-1905)

Thomas Dorman (1905-1906)

Thomas J. White (1906-1906)

Hubbard C. Lockwood (1906-1906)

John Thorwald Kiarskon (1906-1909)

Leroy C. Loughborough (1909-1910)

George E. Loughborough (1910-1912)

Charles L. Ormsby (1912-1912)

Edmund B. Ryder (1912-1912)

John Knott ( -1913)

Joseph A. Blais ( -1915)

William J. Conklin (1915-1916)

Frank L. Thompson (1916-at least 1917)

John P. Ross (1918-1918)

Adam A. Emeigh, Jr. (1918-at least 1920)

Fred Hainsworth ( -1921)

Israel H. Southworth (1922-1922)

Daniel A. Sullivan (1922-1923)

Thomas J. Murray (1923-1923)

Leonard H. Bodine (1923-at least 1925)

Charles H. Eldridge (1926-1926)

Lenorel S. Hill (1926-1927)

Anthony George Zuius (1927-1930)

George H. Tooker (1930-1930)

Dana L. Burt ( -1933)

Robert L. North (1933-1938)

William J. Conklin (at least 1914- )

Edward Steiger (at least 1939-at least 1942)

2nd Assistant Lighthouse Keeper

John Simpson (1921-1921)

Harry B. Dean (1922-1923)

John J. White ( -1925)

Charles H. Eldridge (1925-1926)

Lenorel S. Hill (1926-1926)

Patrick F. Murphy (1926-at least 1927)

Fred J. Worth ( -1928)

George H. Tooker (1928-1930)

Henry C. Gilman (1930- )

William O. Chapel (1930-1930)

Frederick D. Thomas (1938-1942)

George W. Moore (at least 1923-at least 1924)

USCG

Andrew J. Simso II (1943-1947)

Gerald K. Ewen (1960-1960)

Leo T. Frechette (1960-1960)

William A. Matthews (1960-1960)

M.L. Price (1960-1960)

Warren M. Fordham (1960-1960)

Stanley H. Fletcher (1960-1960)

Frank O. Miller (1960-1961)

Peter E. Karpovich (1960-1961)

Philip A. Hollis (1960-1961)

Gary P. Mitten (1961-1962)

Ervin C. Paul (1961-1962)

William Appling (1961-1963)

John Leckie (1962-1963)

Seward A. Shuman (1962-1963)

Thomas W. Conatser (1963-1963)

Charles W. McKnight (1963-1964)

Robert M. Shad (1963-1964)

Dennis G. O'Bosky (1963-1964)

Richard Mizenko (1964-1964)

Robert C. O'Donnell (1964-1965)

Robert S. Hommel (1964-1965)

Kenneth B. Normington (1964-1966)

Thomas A. Meeker (1965-1965)

Raymond G. Waldman (1965-1966)

David F. Teada (1965-1967)

Wendell D. Richardson (1966-1966)

David W. Neal (1966-1967)

Richard K. Lutz (1967-1968)

Jerome Hofgaard (1967-at least 1969)

Robert W. Butel (1968-1968)

Roland W. Ludington (1968-1968)

Mark Gartland (1968-at least 1969)

James C. Walker III (at least 1954- )

John B. Gray (at least 1959-1960)

Thomas L. Poston (at least 1959-1960)

Historical Light List Characteristics

| Year | Characteristics | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|

| 1905 | AlF W Fl R 15s. W131/2, R131/2. | LHB Light List (Atlantic): 335 |

| 1908 | LHB Light List (Atlantic): 354 | |

| 1915 | AlF W Fl R 15s. W14, R14. fl 1. | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 445 |

| 1917 | AlF W Fl R 15s. W12, R12. fl 1. | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 457 |

| 1920 | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 477 | |

| 1927 | AlF W Fl R 15s. W13, R13. fl 0.6. | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 490 |

| 1931 | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 455 | |

| 1935 | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 536 | |

| 1940 | USCG Light List (Atlantic): 510 | |

| 1943 | USCG Light List (Atlantic): 640 | |

| 1945-1947 | ||

| 1950-1952 | AlF W Fl R 15s. W13, R13. fl 0.5. | |

| 1953-1955 | USCG Light List - Vol. I-VI: 710 | |

| 1957 | ||

| 1959-1960 | USCG Light List - Vol. I-V: 775 | |

| 1961 | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 775 | |

| 1963-1965 | AlF W Fl R 15s. fl 0.4. W13 R13. | |

| 1966 | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 973 | |

| 1969-1971 | ||

| 1972 | AlFl WR 30s. W13, R13. | |

| 1973-1979 | AlFl WR 30s. W17, R13. | |

| 1982 | AlFl WR 24s. W16, R12. | |

| 1987 | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 20390 | |

| 1990-1992 | AlFl WR 24s. W17, R14. | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 20090 |

| 1993-1996 | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 21340 | |

| 2004 | AlFl WR 24s. W18, R15. |

Historical Light List Audible Fog Signals

| Year | Primary Signal | Backup Signal | Reference Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1905 | 3d-class Daboll trumpet; blasts 3 sec., alternate silent intervals 2 and 32 sec. | None | LHB Light List (Atlantic): 335 |

| 1908 | 3d-class Daboll trumpet; blasts 3 sec., silent intervals alternately 2 and 32 sec. | LHB Light List (Atlantic): 354 | |

| 1915 | 3d-cl. reed horn; gp. 2 blasts every 40 sec.: 1st blast 3 sec., silent 2 sec., 2d blast 3 sec., silent 32 sec. | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 445 | |

| 1917 | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 457 | ||

| 1920 | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 477 | ||

| 1927 | 2d-cl. reed horn; gp. 2 blasts every 40 sec.: 1st blast 3 sec., silent 2 sec., 2d blast 3 sec., silent 32 sec. | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 490 | |

| 1931 | HORN, 2d-cl. reed; gp. 2 blasts every 40 sec.: blast 3 sec., silent 2 sec., blast 3 sec., silent 32 sec. | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 455 | |

| 1935 | USLHS Light List (Atlantic): 536 | ||

| 1940 | HORN, 2d-cl. reed; group of 2 blasts every 20 sec.: blast 2 sec., silent 2 sec., blast 2 sec., silent 14 sec. | USCG Light List (Atlantic): 510 | |

| 1943 | USCG Light List (Atlantic): 640 | ||

| 1945-1947 | |||

| 1950 | HORN, diaphragm, air; group of 2 blasts every 20 sec.: blast 1 sec., silent 4 sec., blast 1 sec., silent 14 sec. | ||

| 1951-1952 | HORN, diaphragm, air; group of 2 blasts every 20 sec.; blast 1 sec., silent 4 sec., blast 1 sec., silent 14 sec. | ||

| 1953-1955 | HORN, diaphragm; gp of 2 blasts ev 20s (1sbl-4ssi-1sbl-14ssi). | USCG Light List - Vol. I-VI: 710 | |

| 1957 | |||

| 1959-1960 | USCG Light List - Vol. I-V: 775 | ||

| 1961 | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 775 | ||

| 1963-1965 | |||

| 1966 | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 973 | ||

| 1969-1972 | HORN, diaphragm; 2 blasts ev 20s (2sbl-2ssi-2sbl-14ssi). | ||

| 1973-1975 | HORN, 2 blasts ev 20s (2sbl-2ssi-2sbl-14ssi). | ||

| 1976-1979 | HORN: 2 blasts ev 20s (2sbl-2ssi-2sbl-14ssi). | ||

| 1982 | HORN: 2 blasts ev 20s (2s bl-2s si-2s bl-14s si). | ||

| 1987 | HORN: 2 blasts ev 20s (2s bl-2s si-2s bl-14s si). | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 20390 | |

| 1990-1992 | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 20090 | ||

| 1993-1996 | USCG Light List - Vol. I: 21340 | ||

| 2004 | HORN: 2 blasts ev 20s (2s bl-2s si-2s bl-14s si). |